Shopping cart

Recent Posts

Subscribe

Sign up to get update news about us. Don't be hasitate your email is safe.

This is the first in a series of short articles about the history of Otjiherero-speaking communities. It is based on oral histories collected by the theologian and missionary Theo Sundermeier, historical books, and South African government documents collected by this author. The purpose of this article is to gather Herero and Mbanderu communities’ reactions to this material and any additional information – confirming or contradicting- about these events to produce a collaborative understanding of Ovaherero and Ovambanderu histories.

Our story begins in the 1880s, when Samuel Maherero and Kanangatie Hoveka broke ties with Kahimemua Nguvauva (HiaKungairi). However, before we start, we need to back up to a time before these tensions within and between Hereros and Mbanderus. Scholars, mainly historians and anthropologists, believe that Herero and Mbanderu people originally formed a single cultural and linguistic unit until the mid-1700s, when the group that would become the Mbanderu trekked into what is now eastern Namibia. Even after this divergence, Herero and Mbanderus continued to intermarry and collaborate against Nama raids from the south, Oorlam oppression under Jonker Afrikaner and his sons, and, eventually, Germans. In 1881, Herero and Mbanderu leaders Maherero and HiaKungairi worked together to defeat Jonker Afrikaner at the Battle of Osona. However, this strong alliance between these two Otjiherero-speaking communities began to fray with the growing influence of German officials and Maherero’s death in 1890.

The passing of such a strong figure as Maherero created a power vacuum, and opportunities for individuals to achieve various goals. Maherero’s nephew, Nikodemus Kavikunua, inherited his vast herds of cattle, which should have cemented Kavikunua’s position as a powerful leader in Ovaherero society. However, Maherero’s son, Samuel Maherero, had other ideas. Samuel Maherero and Kavikunua were personal rivals – according to oral traditions collected by Theo Sundermeir, Samuel was sleeping with Kavikunua’s wife. One can imagine that Kavekunua’s inheritance of Maherero’s wealth and status must have added considerable fuel to this already ignited fire. Here was a chance for German Governor Theodor Leutwein to exploit this rift within elite Herero society. Taking advantage of Samuel Maherero’s thwarted ambitions, Leutwein imposed the western concept of primogeniture – direct descent and inheritance from father to son – to justify creating Samuel Maherero as Paramount Chief of the Herero. Not only did this contradict practices of dual descent with Otjiherero-speaking society, but it also undermined cultural

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”2295″ img_size=”large” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]power politics in which leadership was spread among clans and influence was earned through personal ability and networks of followers, underpinned by cattle wealth.

HiaKungairi, along with many other Herero leaders, objected to Samuel Maherero’s usurpation of power, but Samuel Maherero was backed by the German colonial regime, with its implicit military superiority. In 1896, open conflict and fighting broke out between the Maherero-German alliance and Otjiherero-speaking leaders, led by Kahimemua Nguvauva. Following Samuel Maherero’s accession to Paramount Chief, Nikodemus Kaviku HiaKungairi nua fled for his life to HiaKungairi, the one leader powerful enough to protect him and stand up to Samuel Maherero. Shortly thereafter, HiaKungairi’s heir, Kanangatie Hoveka, defected from his uncle’s camp to the side of Samuel Maherero and his German associates.

What prompted Hoveka to take this drastic course of action? On the one hand, his actions make little sense. He was HiaKungairi’s heir. First, and most obviously, Hoveka’s defection would have put his inheritance of Nguvauva’s livestock and status at risk. Second, as Nguvauva’s legitimate heir, it would have been in his interests to support Nikodemus Kavikunua’s claim as Maherero’s successor as his analogous counterpart. On the other hand, perhaps there were compelling factors that spurred Kanangatie Hoveka to make such a risky move. It is possible that, given German military power, Hoveka believed that it might serve him best to preemptively cultivate good will with Leutwein, who seemed to be the new power broker in the region, and his client, Samuel Maherero, rather than face the consequences of losing to them. In other words, Kanangatie Hoveka may have believed that this was the best way to secure his own position and the wellbeing of his people. Nevertheless, existing evidence does not clarify his reasoning.

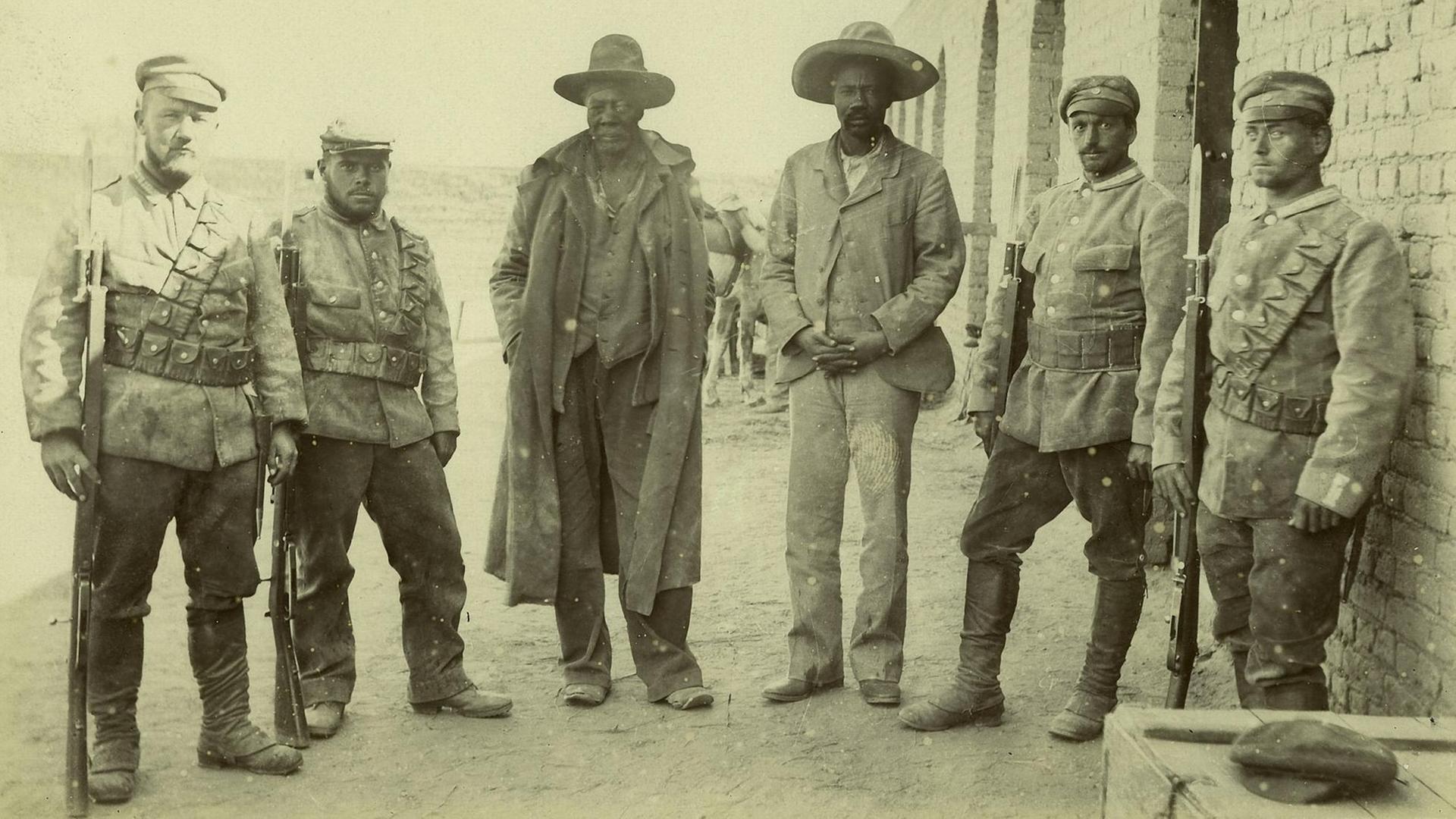

HiaKungairi surrendered to German forces in May 1896 and, along with Nikodemus Kavekunwa, was executed a month later. Shortly before his death, HiaKungairi made a prophetic curse against Samuel Maherero, Kanangatie Hoveka, and their followers in which he forecasted the total destruction of Otjiherero-speaking society. This curse seems to have taken effect almost immediately. First, Kanangatie Hoveka’s gamble did not pay off. He was never recognized as a chief, much less Mbanderu Paramount, by German authorities. Filled with remorse by his treachery, he attempted to rectify his wrongs by allying with Nama leaders against the Samuel Maherero-German alliance. However, he was poisoned to death before he could fully enact this plan. It seemed that Samuel Maherero’s path to unopposed leadership within Otjiherero-speaking society was clear. However, the devastating Rinderpest epidemic broke out in South West Africa in 1898, impoverishing Herero and Mbanderu communities, and making them vulnerable to German depredations. And, of course, the Herero-German War of 1907 and its shocking genocide seemed to fulfil HiaKungairi’s curse to an almost unfathomable degree.

Nevertheless, the events of 1904-1907 were hardly the end of the political controversies unleashed by Samuel Maherero’s alliance with the Germans and Kanangatie Hoveka’s move to their side. When the Herero-German War broke out, Nikanor Hoveka, Kanangatie’s nephew (and[/vc_column_text][vc_text_separator title=”Please read on, you are about to finish” i_icon_fontawesome=”fas fa-braille” i_color=”black” i_background_style=”boxed” i_background_color=”white” i_size=”lg” add_icon=”true”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

presumably his heir?) controversially sided with Samuel Maherero. The Nguvauva faction now considered the Hovekas to be treacherous usurpers and refused to follow Nikanor into battle against the Germans. Instead, they organized under another of HiaKungairi’s nephews – Nikodemus Nguvauva – and relocated to Bechuanaland. When South African officials recognized Nikanor Hoveka as Mbanderu Paramount Chief after occupying South West Africa in 1915, Nikodemus Nguvauva’s followers in Bechuanaland agitated among Mbanderus in South West Africa to overthrow Nikanor Hoveka. They based their opposition on a well-known prophecy made by Tswana Chief Mathibe around 1896 that an Nguvauva would return to rule the Mbanderus in South West Africa, and used this as a rallying point for those Mbanderus disaffected with Hoveka leadership. As we will see in the next article in this series, tensions among and between Hereros and Mbanderus would come to a head in disputes over leadership and territory following the creation of Epukiro Reserve in the 1920s.

Comments are closed