Shopping cart

Recent Posts

Subscribe

Sign up to get update news about us. Don't be hasitate your email is safe.

Omuimbure womuhiva (traditional performer) Wilfred Tjiweza ( Photo W. Wiggers Collection )

As far as we know there are few historical recordings of omitandu. Yet some performances were recorded by the German adventurer Hans Lichtenecker who travelled to South-West Africa in 1931 to create an “archive of races”.

Anette Hoffmann

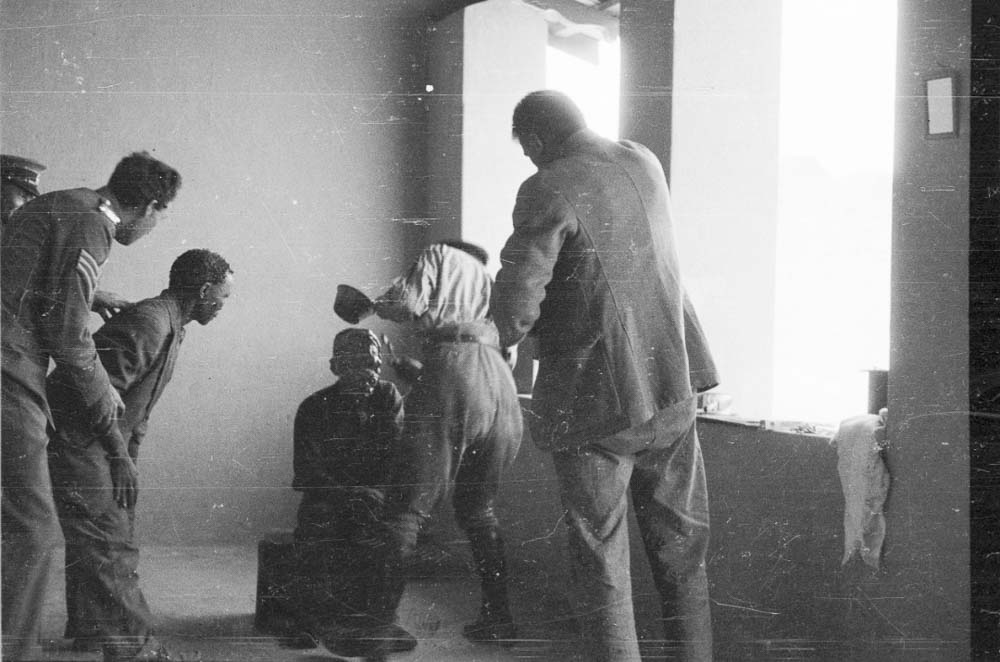

For this purpose he made life casts of people’s faces, hands and feet, took photographs and measured people. For the Phonogramm-Archive in Berlin, Germany, he produced sound recordings with a portable phonograph. Many of the historical recordings speak of the dismay and immense indignity that was caused by objectification of individual people as “racial types.” This especially applied to the process of making casts of people’s heads or faces with a waxlike mass in police stations and on farms.

Some of the audio recordings produced by Lichtenecker contain omitandu performed by Wilfred Tjiueza, who worked on a farm close to Windhoek. The recordings were digitized for my research project in 2007 and translated by Rhyn Tjituka and Renathe Tjikundi in 2008.

On these recordings Wilfred Tjiueza’s beautifully codified performances were preserved. Yet his songs came to be stored in the Berlin archive as ‘indigenous voices’. The translation of his and other recordings allowed comments on Lichtenecker’s project to surface. Speakers referred to their living conditions in the country in 1931. Wilfred Tjiueza used the specific license for critique that comes with the genre of omitandu.

It has not been possible to ascertain much detail on the circumstances surrounding the recordings produced with him at the Lichtenstein farm, except Hans Lichtenecker’s description of testing the phonograph and the camera as well as the casting material and technique in his diary. Photographs from Lichtenecker’s collection show the casts being made of Tjiueza (see below). His niece Rosa Kandanga told me in 2008 that her uncle was a highly estimated performer of omitandu and other genres of the oral repertoire.

Two of his recorded omitandu represent a moment of exceptional artifice. Wilfred Tjiueza characterised two historical figures in the mode of using nearly analogous elements: Chief Zacharias Zeraua (-1915) and Major Victor Franke (1866–1936). Both were leading personalities in the German-Namibian War.

Their omitandu portray Zacharias Zeraua and Victor Franke with regard to their resemblance; Tjiueza’s performance characterises them referring to the same place names, and striking elements from Franke’s omutandu were inserted into Zeraua’s omutandu.

“He looks like one from Kandingua’s house who had such a nice laugh

As if he were Kandingua with such a nice laugh

Why did you return from Namaland?

. . .

He who was with Tjihinamaparero’s people

And the next day with Omaruru’s people

. . .

At Karukua’s stone, which is passed by one of Tjamuaha’s people

The home of the person inside it, he came

. . .

Near the mimosas of Mujemua’s sheep

Near the mimosas of Mujemua

Near the belt of . . .”

“Zeraua, Zeraua, Zeraua, in the new year, in the new year

Zeraua, Zeraua, why did you come?

. . .

He who was with Tjihinamaparero’s people

And the next day he stopped by Omaruru’s people

At Karukua’s stone that sounds like Tjamuaha

. . .

Our large river

That runs to the Mujemua’s mimosas

Please, at Mujemua’s mimosas

At the ornate belt . . .”

The cited verses refer to significant battles of the colonial war in which both men fought, though on different sides. The question “Why did you return from Namaland?” speaks of Franke’s ride to Omaruru from southern Namibia, where he had fought against rebel Nama troops, and thus refers to the Herero people’s defeat and loss of the town of Omaruru. As to why Victor Franke is associated with laugh of Kandingua, a chief in Omburo (in the nineteenth century), remains unclear to me. Franke’s laugh, a personal trait, or the laugh of a victor, pervades the characterization of Zeraua: while Franke was distinguished after the war in Germany. Zeraua’s defeat was dramatic. He capitulated, was taken to court by the German colonial power; he was accused of killing white settlers and died without being allowed to return to Otjimbingwe. Franke’s omutandu is still performed today; the characterization of his laugh has been passed down to the omitandu for his descendants in Namibia.

The omitandu localize several of the places where battles took place: Omaruru, Tjihinamaparero, and Okahandja. After Franke’s company defeated the Herero in Omaruru, fighting ensued sixty kilometers away in Tjihinamaparero. Tjiueza’s performance alludes to their participation in these battles. The parallelism of the two characterizations is by no means random. It refers to corresponding lives and social similarities as the result of practices—in this case, of warfare. In the recording one encounters Wilfred Tjiueza’s astute response to Lichtenecker’s racialising research: Tjiueza’s recitation objects to the racial model underlying Lichtenecker’s research. In his performances on Zeraua and Franke, the difference between a German military man and the Herero chief is not absolute, does not manifest in terms of skin color or facial features. Tjiueza’s critique is codified and bold at the same time; he theorises the similarities and differences of those two men as social qualities that are shown to be historically determined, and formed through practice. Tjiueza’s position on colonial rule is heard in various recordings: as a response to the fable that was presented by a young farm worker, which speaks of the impossibility of shaking off the burden of colonization, he offers a version of the story, which ends with throwing off the conqueror.

Though the town of Okahandja is not mentioned by name, codified fragments from well-known stories do refer to this location: the mimosas of Mujemua, Kapehuri’s belt, Karukua’s stone. These fragments represent significant elements in the omitandu for Okahandja, as the seat of the Maharero family and thus an important hub of power within the Herero societies of the twentieth century. On the one hand, the town is of pivotal meaning as a center of power; on the other, it is remembered as the location where the war against the German Schutztruppe begun, and thus also as a site of initial triumphs. Yet Okahandja is also a terminal point: it is the place where chiefs are buried and where the annual memorial celebrations are held. Two of the crucial elements of these omitandu that characterize Okahandja speak of the ambivalent faces of power, embodied by the chiefs who were based in Okahandja: while the mimosas point to an inheritance dispute and to Maharero’s clever solution in the case, the stone that speaks refers to Maharero’s16 jealousy and to the purported murder of his nephew. His jealousy was founded on suspicions that the nephew was engaged in an affair with the wife of Maharero, and the latter is said to have had the lifeless body tossed from an elevated rock.

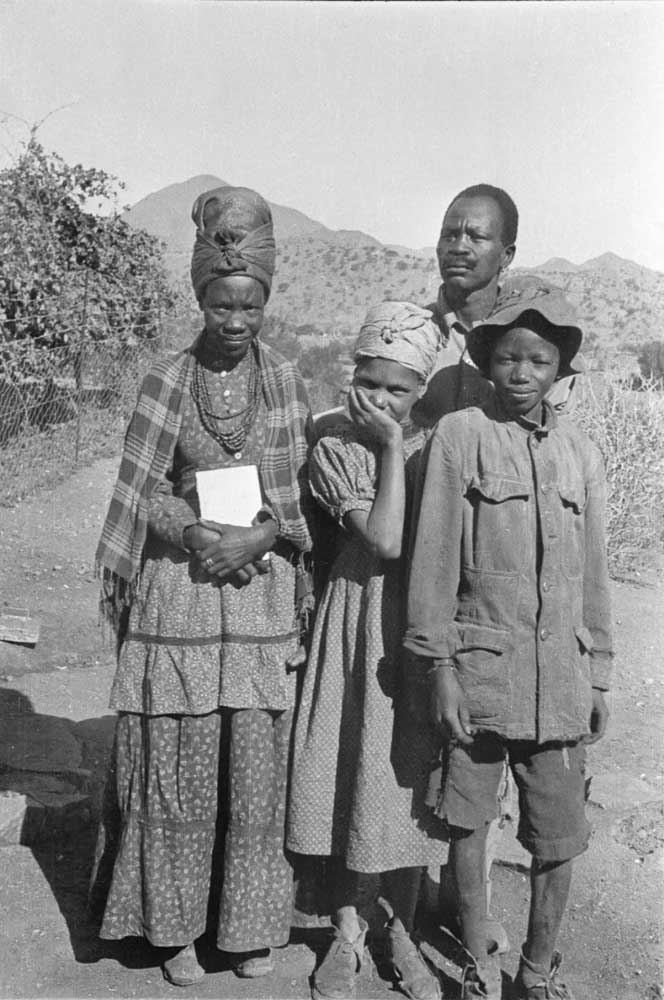

Wilfred Tjiueza with his family on the farm in 1931. Photo W. Wiggers Collection .

The elements of the omutandu for Okahandja, of which only three have been named here, create ever-new formations of a poetic sculpture of a place: each reconfiguration changes the representation of its qualities. By means of naming the places, or rather their allegorical indicators, the progression of intersecting life paths is poetically interwoven, which thus extends beyond a mere representation of the corresponding characters of two warriors: the most dramatic moment in these omitandu is probably the irreversible change of the landscape that is conceived as social and the Herero society.

Here the tree of ohorongo referring to Okahandja where the war began became the tree of ozongonga. Ozongonga, (small watersnakes) refers to the Waterberg and thus (also) to the loss of the war. From there, Ovaherero fled to the neighboring British Bechuanaland through the waterless Omaheke region. In the two corresponding omitandu that portray Zeraua and Franke as characters formed by the war, the dramatic re-inscription of the social landscape by this war is illustrated: “at the tree of the Kudu that became [the tree of] ozongonga.” The alteration of the land of the Herero into a warscape is irreversible, as is the expropriation of the survivors. The resulting colonial power structure allowed for the objectification of colonized people as research material for traveling adventurers like Hans Lichtenecker. Tjiueza’s poetic response tells us that this did not come to pass without objection.

Comments are closed