Shopping cart

Recent Posts

Subscribe

Sign up to get update news about us. Don't be hasitate your email is safe.

They have him pinned down, several men, and they repeatedly beat him. They beat him again and again. His screams often to pause the beatings, but they resume. And it continues. Amid all of it he is being asked questions.

“Please my master,” he says amid screams as another voice retorts, “you know right…you know,” and the question and statement are repeated during breaks in the lashing. “I am being beaten over my wife,” he says and a question follows. “ Who does what?”

“Whom I do not get along with.”

This exchange is viewed from a second video that went viral from 12 October 2020, showing several Otjiherero-speaking men in the process of punishing a peer. The man was pinned down by several men, including one who was kneeling on his back, and another using a cane to beat him.

One of the peers recorded the video and shared with others, who were not present to witness what some in the community consider a clandestine cultural practice to restore good conduct and others claim has never been part of the Herero culture in the first place.

Among members of the Otjiherero-speaking communities, this way of Oukura is polarizing views in pretty much the same way all traditional practices of communities that are modernising.

Genesis 17: 10 “This is my covenant with you and your descen- dants after you, the covenant you are to keep: every male among you shall be circumcised”

The Bible

Some historians consider beating a peer barbaric and outdated, while others acknowledging the spirit of modern times say it shoud be done on the down low (clandestinely) as had always been the case. Punishing a peer never had humiliation as one of its designs: this they all agree with.

Those saying the practice is taboo appear to lean heavily on what they consider as propriety. Those who say it is custom caution that it was always administered as a last resort to correct unacceptable conduct.

Understanding Oukura

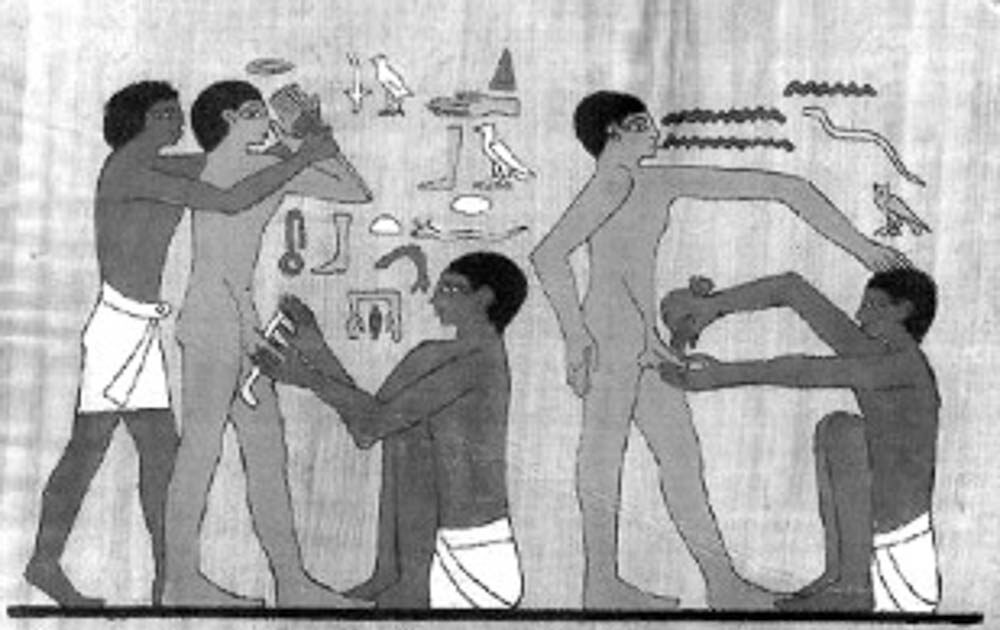

Also called my “foreskin,” Oukura is one of many institutions that contribute to the overall harmonious governance of Herero-speaking communities. This particular institution is build around a rite of passage called circumcision, through which every boy or man goes. Those who are circumcised the same year or over a number of years considered as the same period are regarded peers (Omakura).

Their peer group would be named after the most prominent person or biggest event that marks the period in time when time they go for circumcision (okuyenda kotjivetero).

In 1960, the Committee on South West Africa headed by Vittorio Carpio attempted to enter South West Africa (present-day Namibia) to investigate ways the indegenous people could be assisted to achieve independence.

South Africa and Botswana both refused to allow the UN committee entry into SWA, and when South Africa eventually relented, the committee ended giving a joint statement with South Africa while its leader, Vittorio Carpio, had fallen ill. But Carpio distanced himself from the joint statement when he had recovered.

This whole saga was one of the biggest developments of 1960 and those circumcised then are called Omakura wOtjiuondo tja Carpio (Karapio).

As Omakura, they will go on into adulthood sharing celebrations and tragedies. A groom will have relatives and peers at his wedding and they will be there when an Ekura (peer) dies, or when he loses his mother, whom they consider their mother too. Among the group’s codes, no peer will beat another or swear at another’s mother, or fornicate with a peer’s wife.

Peers will eat his cow for every transgression until he is left with nothing. For some transgressions, the Omakura penal code is uniform. But for others, it is not.

John Kaira gathered his father and mother inside a house, had a gas cylinder open and leaking gas into the house while holding a lighter in his hand. He sat both his parents on a bed and asked them to hand over their Toyota Landcruiser’s key and N$ 3000 in cash or risk being blown up. John had been pulling stunts similar to that on his parents for a while, but this particular one was a prank to far.

His traumatized traditional parents knew that this was one case for his peers. Instead of eating his cow, they took him out to the veld and gave him what some Omakura call a good hiding. They asked as they beat him whether he would repeat any stunt against his parents and only stopped after he repeatedly said he would not.

He has never bothered his parents again since then.

A Clash with Modernity

Among the methods Omakura use to reform a delinquent peer are some that modern laws consider anywhere from being extremely brutal to barbaric, inhumane, degrading and in the same light as tortue, which are all considered unconstitutional. What Otjiuondo Tjotungava peers did in October 2020 would be considered assault, aggravated assault or even torture in Namibian law.

Since the advent of democracy and constitutional order in Namibia in 1990, a person’s dignity became inviolable. Beating any person has become unconstitutional.

An AJA Ismael Mahomed judgment put corporal punishment in its appropriate place: the dust bin of history.

“ It accordingly follows that even if the moderation counselled or comtemplated in some of the impugned legislation or practice succeeds in avoiding “torture” or “cruel” treatment or punishment, it would still be unlawful if what it authorises is “inhuman” treat- ment or punishment or “degrading” treatment or punishment,” Mahomed found in his judgement on corporal punishment.

Justice Ismael Mahomed, 5 April 1991 judgment.

He had weighted Article 8, Chapter 3 of the consti- tution, which enshrines respect for Human dignity against the practice and its end-goals.

That article says every person’s dignity shall not be violated in all proceedings and a person shall not be tortured or put through inhuman or degrading treatment.

Justice Mahomed found Section 292, sub 4 of the old Criminal Procedure Act, which ordered beatings to be done in private, and Section 294 of Act No. 51 of 1977 which prescribed seven strokes with a cane, without stripping the offender naked as unconstitutional.

Otjiherero speaking communities (Ovaherero, Ovambanderu, Ovahimba, Ovazemba, Ovahakaona, Ovatjimba) all have the institution of Oukura and observe certain rites and activities under its banner. Everyone of these communities agrees that Oukura is an insti tution founded on respect for one another and for assisting each other.

Traditionalists in Kunene Region like Hirende Kavari and Uerimanga “Papa G” Tjijombo say a deviant or perverted peer, whose conduct is so unbecoming as to frighten the community or poses a risk to someone’s life, would be tied into a position similar to a person inside a straight-jacket before being left to the ants to bite him. Another way was to tie a very sharp stone to the person’s toe while restraining him.

Most peers, who have survived these punishments had gone on to concede that their conduct improved. It was meant to promote respect and blunt the anger, rage or deviance.

Herero traditional priest Ngeke Katjangua says omakura had an “ ezuko repenye ave umbu okatjunda, ave zepa onyanda nokupikasana, okutara kutja nani omakura.” That means that they lit a fire inside an enclosure, where each peer entered naked and they wrestled each other to the ground to see each other’s temperament. Kapika Uzeraije Tjazerua, former Aminuis Constituency Councillor, now late, Erwin Uanguta and Omatjete traditional councillor Urbanus Uaseuapuani say this was the only time peers will physically touch each other.

But Uanguta says beatings were done in violation of tradition, and peers conducted them in a secret and secluded place to correct wrong behaviour without humiliating a peer in public.

At Odds with the Times

Modern laws and the ways of Ovaherero communities have been at odds with each other in several respects. Practices like Okujepisa, polygamy, corporal punishment in homes and of late punishing peers, derive from tradition. These traditional practices appear out-dated in modern societies. Traditionalists continue to argue that the community’s customs had derived from centuries of wisdom and mirror religious text like the Holy Bible, and serve the greater good. Critics find them to be backward and unsuitable in modern society.

Traditionalists bemoan the continued erosion of their tradition and culture. They find democracy and the rights dispensation to be at odds with long-held customs, which had helped make life predictable for these communities for centuries. Is it the end today when a father trying to punish a child is reported to a Child Welfare unit in the police?

Comments are closed